"And we will all call him Liam, won't we?"

This article is cross-posted from Helen Joyce's website with her permission

By Dr H Joyce – 17 Nov 2022 – View online →

I’ve recently returned from a trip to Dublin for “Women’s Space to Speak”, an event arranged by campaign group Women’s Space Ireland and inspired by the highly successful events in the UK run under by Woman’s Place UK and by Kellie-Jay Keen, aka Posie Parker. With room for 200 people, it was a sell-out—and a huge success. You can view the programme here, and read write-ups in the Sunday Times and Irish Law Gazette.

Most of the audience, and all of the speakers, were women. But among the men in the audience were Paddy O’Gorman, a veteran radio broadcaster who recently produced a podcast from outside Limerick women’s prison, where three men with gender-recognition certificates stating their sex as female are being held, and Cathal Mac Coille, who writes for Irish-language news service Tuairisc Nuacht. Eilis O’Hanlon, a columnist for the Irish Sunday Independent, was there too, and Colette Colfer, an academic who writes occasional pieces of journalism about religion, was among the speakers. It felt like an important milestone in Ireland’s progress towards the sort of united feminist resurgence that will be needed to push back against the encroachments of gender self-ID.

If you are not a subscriber to my weekly newsletter, you might like to sign up for free updates. I hope that in the future you might consider subscribing.

I was one of two people to talk about the impact of gender-identity ideology in schools. I billed my talk as a message from the future—ie, the UK, where schools have been indoctrinating children, and creating and promoting gender distress, for close to ten years. The result is visible in a veritable epidemic of trans identification among young people. This is what’s in store for Ireland, I said, unless it stops schools from adopting a similar ideological approach.

The other speaker on schools was the Rev. Professor Anne Lodge, an academic, former teacher and Church of Ireland priest. Her fascinating talk was about the extremely strong rights the Irish Constitution gives to parents, in particular concerning the moral, intellectual and ideological formation of their children. Irish parents, she said, have the power to stop schools indoctrinating their children—as long as they realise that, and fearlessly use it.

I’ve been pondering ever since: if I could choose, would I prefer to have full gender self-ID combined with strong parental rights, as in Ireland—or the UK’s much tighter gender-recognition regime combined with schools that increasingly seem to view parents as bigoted obstacles to indoctrinating children, and are willing and able to act in ways they know that parents would hate? I think I might choose the Irish combination. As I started my talk by saying, schools are the single most important production site for the next generation of gender ideologues. If you sort out schools you’re a good part of the way towards sorting the problem out generally. If you don’t, you won’t be able to sort it out at all.

The rest of this week’s issue is a somewhat expanded and tidied-up version of my speaking notes, which I’ll be sharing with the organisers of the Irish event for circulation to attendees.

The first thing I want to say is that both gender theory and gender distress are a social contagion. That doesn’t mean they’re “not real”; it means that they’re part-created and part-shaped by the culture we live in.

One of the questions I’m most often asked, even by people who accept the social-contagion hypothesis, is: how many people are “really” trans, rather than caught up in a craze? I answer that I don’t think anyone is “really trans”, in the sense these people mean: there isn’t some tiny number of people who “truly are” members of the opposite sex inside—no one is actually a member of the opposite sex; that statement makes no sense.

Trans is an umbrella term for a whole bunch of different things that are linked only by the notion that there is a reasonable way to use sexed terms—man, woman, male, female, boy, girl—that doesn’t simply refer to our evolved mammalian biology. What do these different groups have in common: middle-aged men who’ve been cross-dressing since adolescence for erotic purposes and now want to do so full-time? Self-hating, self-harming teenage girls? Highly effeminate little boys destined to grow up gay? Abused children who have dissociated from their bodies? Autistic children who misinterpret their non-conformity and sensory issues as alienation from their sexed bodies?

Nothing, except that all are unusually susceptible to believing the claim that that it is possible to be a physiologically normal boy or girl, but in some more real, more true sense be a member of the opposite sex. And that’s far from a full taxonomy of the groups we’ve seen identify as trans over the past decade or two.

The thought “I’m not really a man/woman” does seem to have occurred spontaneously to occasional people in different places and times. Those rare people didn’t interpret that thought literally—or expect everyone else to go along with it. But now it has been packaged up into an overarching theory—that what makes everyone who they are, in particular when it comes to which sex category they fit into—is inside the head, not written on the body.

This thought is an example of what Richard Dawkins called a meme—an idea that spreads from mind to mind, evolving as it goes. And it’s a really successful one.

Just why is an interesting question. One reason is that we live such dematerialised lives now, sat in front of our computers all day, and rarely going out. Many young people spend a great deal of their time identifying with avatars that can change sex (and other characteristics, even race or species) at the click of a mouse. Delayed child-rearing and smaller families mean longer periods living as adults before procreation drives home the irreducible differences between the two sexes. Another consequence is that many more adults are deeply ignorant about children, and unaware of how willingly they take on trust whatever authority figures tell them.

This meme has also been given velocity by inaccurate comparisons. The right to self-identify your sex and force everyone else to play along is presented as a civil-rights battle, the latest in a long line running from the ending of slavery through women’s suffrage to the black civil-rights movement in America and most recently the legalisation of gay marriage. If you don’t look too closely, “trans rights” appears to be another instance of Martin Luther King’s famous aphorism: “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

So people are primed to think of opposition to trans ideology as yet another in a long line of prejudices, when a much more accurate comparison would be with eating disorders. Gender distress is a societally created disease that ends up overtaking a person’s thought processes. We know such diseases exist: they’re called “culture-bound syndromes”. We know they can be elicited and moulded; we know that they are contagious.

In other words, they can be taught. People learn everywhere, all the time, but in schools learning is the entire aim. It’s my contention that in roughly the past ten years in the UK, anti-bullying, anti-prejudice, equality and human rights policies and approaches, and above all relationships and sex education (RSE), have been hijacked to teach trans ideology.

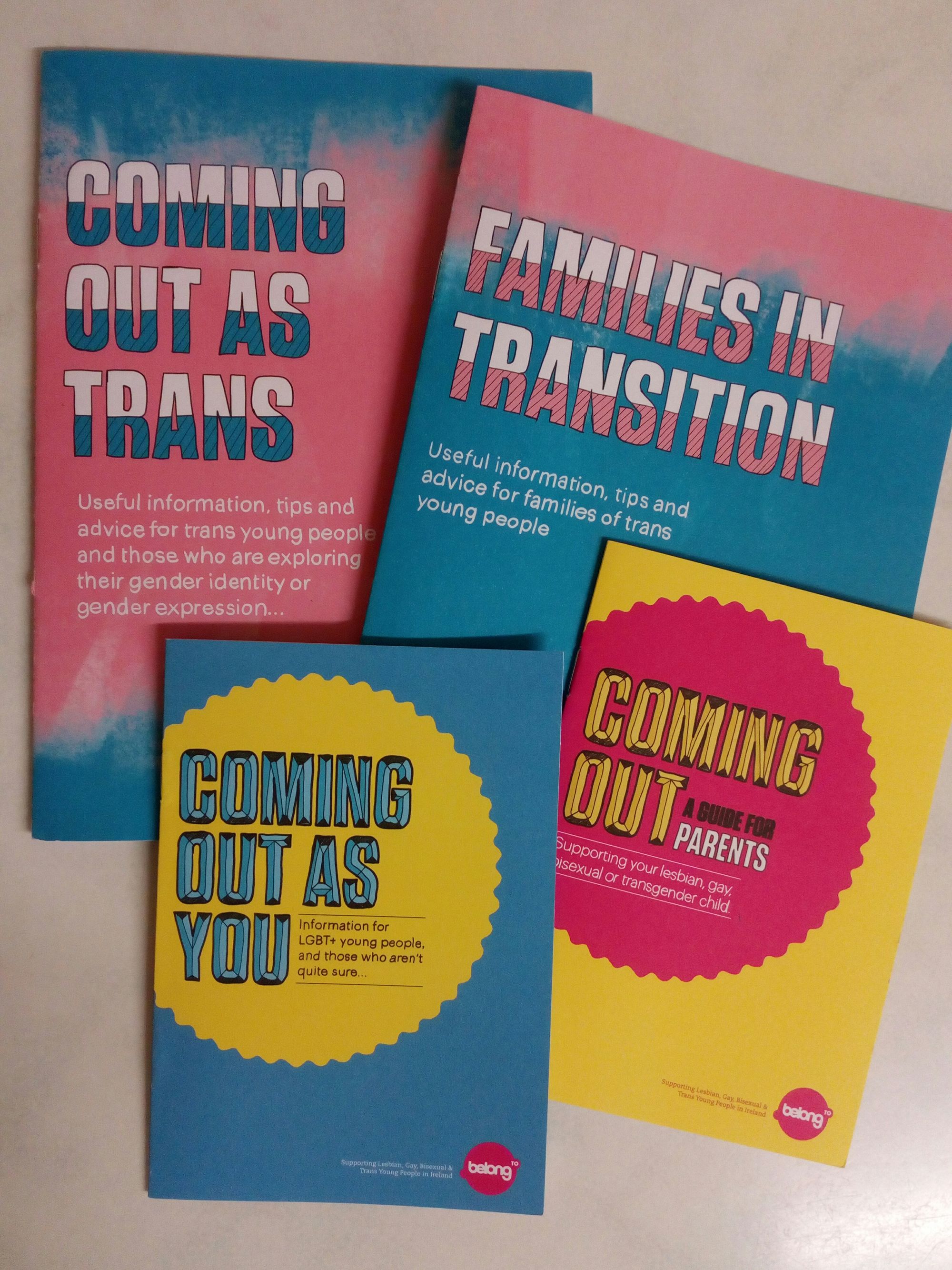

In the UK RSE is now compulsory, and there is official guidance but no official curriculum. The result has been wholesale capture by lobby groups, who produce material that they sell (sometimes literally—plenty are commercial operators) as progressive, inclusive and in line with government demands. Some also put free lesson plans and videos online for teachers to pick and choose from.

Among them are Stonewall, the Kite Trust, the Proud Trust, Mermaids, Gendered Intelligence, Pop’n’Olly—all, in my opinion, as bad as each other. You can read some detailed analyses on the websites of Safe Schools Alliance and Transgender Trend (here and here). As these analyses demonstrate, much of the material now used in UK schools is scientifically inaccurate, ideologically biased and often blithely oblivious to any consideration of child safeguarding.

Some of it is aimed at little children, and seems specifically intended to prevent children from ever reaching an important developmental milestone: the acquisition of what is called “gender constancy” (though sex constancy would be more accurate). Before this stage, a child thinks the difference between boys and girls is about hairstyle, clothing and other aspects of self-presentation, and that by changing these, a boy can become a girl and vice versa. After it the child understands that sex is fixed and determined by the body, no matter what people wear or do. I cannot be sure that activists are consciously seeking to disrupt this developmental process, but it certainly looks like it.

I’ve written about one of the very worst external providers, Pop’n’Olly, for the Daily Express. And in issue 5 of this newsletter, I wrote about a particularly awful video produced by Ireland’s largest teaching union, INTO, entitled “Facilitating a Social Transition”. After significant criticism, that video appears to have been stealthily taken down, and journalists who have asked why have got no answer.*

Here’s what I said about it previously:

Judging by animation style and the book it references (“Introducing Teddy: A Story About Being Yourself”), it’s intended for the earliest years of school—when children’s understanding of sex as a physical, bodily reality has probably not yet firmed up. The approach the video suggests would radically disrupt that emerging understanding.

The teacher answers the questions: “So boys can change into girls?” and “Girls can change into boys?” with bald “yeses”. Imagine how terrifying this could be. A child might naturally ask himself or herself: could this happen to my friends? Could it happen to me? And how potentially damaging to the relationship with parents, too—a child who repeats the message of this lesson at home may well find that mum and dad disagree.

There’s also equally pernicious material aimed at older children. Getting in early has the advantage that you may be able to disrupt children’s understanding of sex as binary and fixed before it ever develops. Teenagers, however, are vulnerable in a different way—they are going through a lot of changes which may seem confusing and unwelcome.

Teenage girls, in particular, seem really susceptible to the idea that sex is an opt-in, opt-out category. One reason may be that female embodiment is in many ways more onerous than male embodiment, and the prospect of opting out may therefore seem more tempting.

Another, for which I’m indebted to Colin Wright (@swipewright), is deceptively simple, and very powerful. As he noted in a previous issue of his Substack newsletter, Reality’s Last Stand, in recent years the formal definition of transness put forward by campaign groups and gender clinicians has been expanded to include simple gender non-conformity (that is, without any distress). From around the same time, the number of teenage girls identifying as trans has soared.

Wright hypotheses a simple but powerful explanation: girls are far more likely than boys to be gender non-conforming. The reason for this is that although gender can be a prison for both sexes, gender rules for girls are much more constraining, and much harder to fit within. Girls are therefore much more likely to be—and to think of themselves as—gender non-conforming. A girl who wonders why she finds it so hard and unappealing to follow exacting and capricious beauty and behaviour standards, and who searches for an explanation online or listens to awful lessons that define membership of her sex as dependent on conformity of stereotypes will discover that she fits the definition of “trans”—even if the idea that she is “not really a girl” had never previously crossed her mind.

Whether these lessons are early enough to disrupt the acquisition of gender constancy, or instead take advantage of the confusions of puberty, they have helped produce a generation of young adults who think that any mention of the fact that sex is binary and immutable is extremely bigoted.

Many UK schools also push trans ideology by supporting “social transition”. Many now think it’s their job to accept unquestioningly any statement made by a child of any age about his or her identity. They will change the child’s name and sex marker in school records on demand; start to use opposite-sex pronouns (or they/them for a child who identifies as non-binary); and allow the child to use facilities such as toilets and changing rooms intended for the opposite sex and to play on the other sex’s sports teams. They will reinforce this social transition by penalising teachers, and perhaps pupils, who fail to use the trans-identified child’s preferred pronouns, or who complain that about a trans-identified pupil’s presence in the other sex’s spaces.

The final way in which UK schools push trans ideology is via school management, record-keeping systems and communications. For example, it’s becoming common to have only “gender-neutral” (that is, mixed-sex) toilets, which is sold as an “inclusive” way to accommodate pupils of “all genders”. This not so subtly suggests to all pupils that sex isn’t real, or at least is trivial in comparison with other personal characteristics.

The extent to which this stuff has become embedded in the school system is incredible. My son recently registered for a sixth-form college, which teaches youngsters aged 16-18. One of the compulsory fields in the form required him to fill in his “preferred pronouns”, with three options: he/she/they. The college already knows his sex from his application form; “prefer not to say” was not an option; and it was impossible to progress to the next question and therefore complete registration without picking a pronoun.

This is not just coerced profession of a belief system that not many people share: it’s normalisation of the idea of identifying out of your sex. I’d go so far as to say that this college is suggest-selling trans identification to all pupils.

When you put all this together, schools in the UK are feeding and fuelling two closely linked social contagions. The first is the idea, or meme, that sex is neither real nor important and gender identity is both of these things. The second is distress about or dissociation from one’s own sex. They’re doing this in lessons, by supporting social transition and by re-organising facilities and systems that used to refer to sex around gender identity instead. The result is twofold: the creation of new little gender ideologues, and the creation of “trans kids”.

You’ve probably heard that trans-identified youth are disproportionately drawn from highly vulnerable groups, such as the autistic, self-harming, anxious, depressed or proto-gay. This is certainly what shows up in data from gender clinics over the past several years. But it turns out that they were just the early adopters: the first to latch onto an ideology that claims to offer a quick, guaranteed fix for every problem, and that promises adherents can be reborn as someone entirely different.

The trans contagion has now moved beyond the early adopters, and is in the population at large. Anecdotal evidence suggests that when children in the UK went back to school after the summer break this year, there was a rush of trans identification in schools. The epidemic is now hitting happy, healthy children with supportive parents and no history of any psychological issues.

Let me tell you two stories I’ve heard in the past couple of months. One concerns a 13-year-old, whose parents got an email from the school shortly after the start of term. What follows is a paraphrased version of parent-school communications, with names changed.

“Dear Mr and Mrs Smith”, it started breezily, before going on to inform them that their daughter, let’s call her Sarah, “now identifies as a boy, so from now on the school will be calling her Sam and referring to her with he/him pronouns. We’ll be updating school records and the information given to exam boards. Let us know if you’d prefer us to keep calling Sam “Sarah, she/her”, in conversations with you. Have a nice weekend!”

This email is extraordinary for several reasons. First, the trivialising tone is totally inappropriate for a communication that landed like a bombshell with the unprepared parents. Second, the way the sender continues to refer to “Sarah” as she, even while explaining that Sarah is now a boy, shows it was written by someone who has no grasp of what they are actually saying. Third, isn’t it incredible that a school thinks it can simply inform parents of something so consequential, without even an invitation to discuss the move?

Apparently, this school used to routinely keep parents in the dark about trans identification, referring to children by their chosen names and pronouns during the school day, but switching back when talking to their families. It stopped that after some particularly dogged parents found out that their daughter had been treated by the school as a boy for many months without them knowing, and made formal complaints.

Since that first communication, the school has told Sarah’s parents that its policy of instant affirmation without any consideration of what parents thought was based on “safeguarding principles”. Trans children who weren’t affirmed were at sky-high risk of suicide, it claimed. But this claim is not only nonsense (see Transgender Trend for a good debunking); it runs directly counter to any justification for keeping trans identification secret from parents. A child sufficiently distressed to consider self-harm or worse is almost certain to hurt themselves at home, not at school, and parents absolutely need to know.

Most incredibly, the school airily mentioned in passing that a tenth of the children on its rolls identified as something other than their natal sex. I’d take a large bet that most of those trans-identified children are female—and that there are pupils at that school who identify as trans among their friends but haven’t told their teachers.

I’d guess, therefore, that around a fifth of all the girls in this perfectly ordinary state secondary school are dissociated from their actual sex. How can the school leadership remain blind to the fact that this is a social contagion? How can anyone?

My second story is also slightly disguised. It concerns a slightly older girl, with a diagnosis of autism-spectrum disorder, from a family that suffered a serious trauma a couple of years ago. She has been demanding that her family affirm her identification as a boy for a while now, and wants to go on testosterone when she turns 16. But the family are unwilling to affirm, both because of her ASD and her trauma, but also because they are convinced this identification is an idea that has come from outside the child.

And so earlier this autumn the child self-harmed. The parents are certain that her aim was to be urgently referred to mental-health services, where she complained about her unsupportive parents. The family is now under investigation by social services, and have been informed that they may be judged unfit to take care of all their children. Wisely, they have splashed out on expensive lawyers, and so the worst may not happen. But this is where the suggest-selling of trans identification to children leads: families in crisis, and loving parents terrified of losing their children.

So what can parents do to resist the encroachments of gender ideology in the classroom? I’d recommend starting with a softly-softly approach.

Have a friendly conversation with your child’s teacher. Explain that you are worried by materials you’ve seen in the press and heard about in conversation with other parents, which seem to you to be scientifically inaccurate and ideologically loaded. Ask if the school works with any outside groups, either by getting instruction in or by using externally produced lesson plans. Ask to see lesson plans.

If the school has a “trans inclusion policy” or similar on its website, read it carefully. Look for what it says on access to single-sex spaces or sports: based on sex or self-identification? Does it say anything about mandating the use of preferred pronouns? If what you find is concerning, tell the school politely that you don’t think it’s right that other children are pressured into accepting their single-sex facilities being used by someone of the opposite sex, or having to pretend they think trans-identified boys are girls and vice versa. Say you think there has to be a way to accommodate everyone: gender-distressed children and all other pupils, without trampling on anyone’s rights. And the big one: say you’re concerned about safeguarding. No teacher or school administrator should ignore that.

If you’re worried about what you find out, and the school’s response, progressing further is best done in a group, if possible. Form a coalition, ideally of different sorts of people—mothers and fathers; religious people and atheists; not all from the same background. That makes it harder to dismiss complaints and worries as the tedious obsessions of white, middle-class mums (this shouldn’t happen, but it does).

It’s really important to get parents involved whose own children aren’t caught up in the trans-identification craze—families that are in crisis must focus on their own child’s need first, and that may well mean not saying anything that risks alienating the child or otherwise inflaming the situation.

And if the school remains obdurate, you’re going to have to check its formal complaints procedures. I know it’s daunting to think of falling out with an institution that’s so important in your child’s life—but we’re talking about children’s safety here. (And as I said in response to a question at the Ireland event: child safeguarding is the responsibility of every adult. This isn’t on children to fix, it’s on us.)

To finish, I’ll share a success story. The first kid I mentioned, the one whose parents got the chirpy email announcing that their daughter is now their son, is now doing well. Her parents told her they had done some research into binders and had become deeply suspicious of the activists’ claims that they are safe. She trusts her parents, and believes they have her best interests at heart—and so she readily agreed to stop binding and get fitted for a really supportive sports bra instead. Even better, discovering that activist material she had previously trusted was so biased and unreliable planted seeds of doubt, and she’s rethinking more than just the binder.

I hope you can see why I say that this contagion is, if not all about schools, very importantly about schools. And the lesson I take from the UK is that, once schools start to push trans ideology in good earnest, it takes less than a decade before no child can be considered immune.

If you are signed up for free updates or were forwarded this edition of Joyce Activated, and you would like to subscribe, click below.

Helen Joyce © 2022

*This video and three others in the series are available on application to [email protected]