Democracy is Worth Fighting For

Iseult White at Women's Space to Speak, 12th November 2022.

Hate crime is horrible. It sends a message to the victim that they, and their kind, their children, their family, their tribe, are not welcome or safe in society. It sends a message that they may be physically assaulted or their property destroyed simply because they possess a characteristic that the perpetrator hates.

I know how it feels. I have experienced that kind of hatred. A number of times. Going in to bars, coming out of nightclubs, or just walking down the street going to the hardware store, hand in hand, with my lover, just enjoying ourselves, enjoying each other.

There is a visceral form of hostility evoked in some men when they see two women who have no need for men in their lives.

Hate like that circumscribes and limits daily life.

So naturally I understand and I applaud the good intentions in legislating against hate crime.

However there is little evidence from any jurisdiction that has enacted hate crime legislation that it reduces the rate of hate crime or decreases the level of tensions between communities. The actions or conduct that underly a hate crime conviction are already criminal, the hate aggravator just makes the sentence more punitive. The threat of a harsher sentence doesn’t deter offenders. Conviction rates are very low. Hate crime is difficult to prosecute. Last year in the UK out of 155,841 hate crime reports only 7% resulted in a conviction. In the preceding 5 years conviction rates halved while hate crime reports doubled.

In their book, Hate Crimes, Criminal Law & Identity Politics authors Jacobs and Potter argue that hate crime legislation itself undermines "social solidarity”. It encourages people to frame themselves within their identity groups. The needs of each group become politicised, and groups compete against each other for criminal justice resources, for protection and support. Professor Neil Chakraborti, director of Leicester University’s Centre for Hate Studies which has worked with more than 2,000 hate crime victims argues that such legislation [1]

"merely exacerbates existing problems, creating divisions among communities of identity rather than highlighting the shared nature of their victimization".

Like many researchers of hate crime they advocate for restorative approaches that have a chance of reducing crime before it happens, rather than punishing the perpetrator when a crime has already been committed.

So I have general concerns about our legislation, but it is the hate speech element of the bill that concerns me the most.

In Ireland the right to freedom of expression is protected under our Constitution, and under EU and international law.

International human rights law recognises that criminalisation of expression should be reserved for only the most serious cases of hate speech.

Freedom of expression gives us the right to seek, receive and disseminate information, art, political speech, ideas of all kinds, without interference by State authority. Free speech is meaningless if it does not include the right to criticize, challenge and profoundly disagree with the State and with other citizens.

The European Court of Human Rights states that the right of freedom of expression applies:

“not only to "information" or "ideas" that are favourably received or regarded as inoffensive …, but also to those that offend, shock or disturb the State or any sector of the population.”

Because restrictions on hate speech can have chilling effects on freedom of expression only the most severe hate speech expressions should meet the criminal threshold of incitement to hatred.

So the question we need to consider is does this law compromise our right to freedom of expression?

In a response to The Irish Times the Department of Justice said that only

“extreme forms of hate speech that deliberately and recklessly incite or stir up acts of hostility, discrimination or violence will be criminalised”.

Already we see the vagueness here. Speech that deliberately and recklessly incites discrimination. It is not clear how high a bar that is.

They do go on to say that

“the right to freedom of expression means individuals can hold and express opinions that others might find offensive or shocking.”

and that

“The legislation recognises that communication is not taken to incite violence or hatred solely on the basis that it involves or includes discussion or criticism of matters relating to the protected characteristics.”

Can we trust these assurances from the Department of Justice? I genuinely don’t know.

It is clear that advocacy and civil liberties groups in Ireland use a very broad definition of hate speech.

Some of you will remember that in November 2020 Amnesty International, the National Womans Council of Ireland and 25 other Irish organisations demanded that the Government and the media deny "legitimate representation" to women and men like you and me, who believe that biological sex is material in life, and that it is a fundamental axis of oppression in the world.

It was a difficult choice for me to challenge Amnesty because in some ways it meant speaking out against my tribe.

But I had no choice. I was raised to believe the right of freedom of expression is a fundamental safeguard in democracy. My family had learned that through bitter experience. My grandfather, Seán MacBride, founded Amnesty to protect the rights of political prisoners, people who exercised their right of free speech to challenge authoritarian governments. His concern for prisoners of conscience came directly from his own experiences as a political prisoner, and from fighting at the age of 14 for the release of his mother, Maud Gonne, from a British prison.

Freedom of expression protects against the rise of authoritarian governments. But for some people it seems that the more diversity we are celebrating in society, the less diversity of speech we are willing to tolerate. They are willing to introduce laws that criminalize legitimate speech.

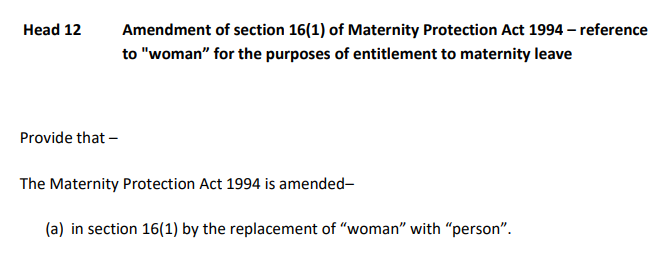

Earlier this summer when Irish citizens phoned into RTE's Liveline to protest at the removal of the word "woman" from the 1994 Maternity Protection Act those citizens were accused of hate speech.

The Irish Council for Civil Liberties claims to stand for free speech. They called the conversation on Liveline “incredibly irresponsible”and joined in with Trans Equality Together saying that a defense of freedom of expression was no excuse for “giving airtime to groups that would deny the basic rights” of a minority community. Exactly the same hymn sheet as the 2020 Amnesty letter.

Ailbhe Smyth, at a reception in the Mansion House hosted by the Lord Mayor of Dublin said

“It is not the role of our national broadcaster to enable or encourage hate speech of any kind.”

Her words were echoed by our Equality minister Roderic O’Gorman.

Open debate on the impact and consequences of legislation is just basic democracy. This extraordinary overreaction demonstrates that at the heart of the state’s apparatus of power are people who are willing to suppress the democratic right to challenge and criticise legislation by labelling such challenges as hate speech, and advocating for the prosecution of that speech as a hate crime.

Later in the summer the IRFU announced their exclusion of men who identify as transgender from playing contact rugby with women, an exclusion supported by rigorous review of the science that shows that trans women maintain their male performance advantage even when they medically transition, and that they remain on average significantly heavier and stronger because they are male, and therefore create a risk of serious injury to women in contact sports.

The ICCL were quick to criticise the IRFU saying trans rights are human rights:

We are left wondering what are the rights of girls and women, because it appears that for the Irish Council of Civil Liberties, girls and women do not have the right to safety on the sports field, or dignity in their changing rooms.

It is organisations like the ICCL and many of the NGOs that signed the letter which Amnesty also signed who will be funded by our government to provide training to the Gardai and the DPP on how hate speech should be defined and prosecuted. So this law will not act in isolation, it will operate within a power structure that has systematically punished and imprisoned women since the inception of this State.

This sash I am wearing is the sash my great grandmother, Maud Gonne, wore as president of Inghínídhe na hÉireann, (Daughters of Ireland) a woman's organization founded in 1900 to bring awareness to the lack of suffrage, recognition and inequality women experienced at the time. It is hard to believe that 120 years later women are afraid to speak a simple truth, the truth that men cannot actually become women.

Of course the men who wish they could become women deserve respect in their daily life, and of course the State should protect them from discrimination. Their rights are human rights. But women’s rights are also human rights and we do have the democratic right to challenge laws that cause detriment in our lives.

So the next question I considered was can we look to the hate crime legislation for protection. I think we can try.

If we look to the protected grounds in the legislation they are very broad.

"Sexual orientation” has the same meaning as it has in the Equal Status Act 2000 - it is defined as heterosexual, homosexual or bisexual orientation.

So no matter your sexual orientation, it should be protected speech to talk about how biological sex is material in your sexual attraction.

There is also the ground of "sex characteristics". This is defined as all physical and biological features of a person relating to their sex. This protection seems to recognise what we already know, which is that biological sex is material in some acts of hatred.

Finally the "gender" ground which just seems to mean "whatever you're having yourself". Everybody is protected against attacks that are motivated by their gender, no matter how they define or express their gender.

So once this law is passed, when you see hate speech directed at you on any of protected grounds: report it. The Gardai record hate based on the perception of the victim that the attack is motivated by hostility or prejudice, based on having a protected characteristic. As we can see some of those characteristics are so broadly defined that they are fundamentally meaningless.

So when this law is passed I will be down in my local Garda Station reporting tweets like this one that urges people to cut up women (who challenge gender identity ideology). It is not ok to promote violence against women.

I will also be reporting Lynn Boylan. Because when an elected official of the State likes a tweet that promotes violence against women they are inciting hatred. TERF is no different from the other slurs like cunt, bitch, feminazi, lezzer, that have been used to silence women since the beginning of time.

I want to encourage you to be a little braver tomorrow than you were today. Be braver about asserting your right to political speech. Sex is material in the lives of both men and women, it is our democratic right to speak about that. Under the new legislation you may be reported for hate speech. You may even be prosecuted. Remember the process is the punishment. Christina Ellingsen will tell you more about that next.

But democracy is worth fighting for. It is worth fighting for every day of our lives.

[1] Chakraborti, N., & Garland, J. (2012). Reconceptualizing hate crime victimization through the lens of vulnerability and ‘difference’. Theoretical criminology, 16(4), 499-514.